Calcium is one of the most debated topics in nutrition, and it brings together several challenges for nutrition research:

- Are randomised controlled trials influenced by baseline nutritional status?

- Do we understand what levels of intake represent true insufficiency and adequacy?

- Is the potential effect of the nutrient modified by other dietary and lifestyle factors?

- Is there a difference between the nutrient as a supplement and a nutrient from food?

The research on calcium and bone health throws all of this at us.

For example, regarding No.1 above, the Women’s Health Initiative found no effect of combined 1,000mg calcium and 400IU vitamin D per day on the risk of fractures over 7 years. But don’t be too quick to judge: both the placebo group and the intervention group had an average daily baseline calcium intake of ~1,1150mg. So, the real comparison was “more of enough calcium vs. more than enough calcium”, not “calcium vs. placebo”. This is a major issue in nutrition intervention trials; all participants tend to have sufficient nutritional adequacy at baseline.

What about No.2 above?

Calcium recommendations have typically been based on calcium balance studies, i.e., looking at when calcium losses are matched by calcium intake. Depending on the analytical approach taken, focusing on calcium balance as a determinant of adequate calcium requirements may result in ranges of anywhere from 500mg/d to 1,500mg/d.

But wait: when has nutrient balance been a good marker for optimal intake? Think about dietary protein: the recommended daily intake is based on the minimum amount needed to maintain a positive nitrogen balance, but this is far from optimal for people who are athletic, older, pregnant, etc.

No.3 above is something we certainly know concerning calcium, that both vitamin D and dietary protein act as strong moderating factors in the associations between calcium and bone health.

Finally, what of No.4 above?

There is evidence that dietary calcium is associated with more favourable bone mineral density in postmenopausal women compared to women obtaining calcium through supplements.

Is there a way to reconcile these issues?

Testing a Food-First Approach to Calcium and Protein

A 2021 study by Iuliano et al. provided answers to several of these questions in an elegant, cluster-randomised trial. In “cluster-randomisation”, the unit of randomisation is not an individual. Rather, a cluster of individuals in a pre-specified group is randomised together. In this case, the study was conducted among permanent residents of residential care homes for the elderly in Australia. Thirty care homes were randomly assigned to the intervention and 30 to the control.

The study deliberately included care homes that served no more than two daily servings of dairy, i.e., participants to have daily calcium intakes of <600mg/d. The intervention targeted achieved daily calcium intake of 1,300mg and 1g/kg/d dietary protein from increased dairy foods specifically. A serving of dairy was defined as 250ml milk, 200g yoghurt, or 40g cheese. The control care homes maintained their usual menus.

The primary outcome was bone fracture incidence over 2 years, while secondary outcomes included time to falls and biochemical indicators of nutrient status and bone turnover.

What Did the Study Find?

Dairy food intake increased from an average of 2 servings to 3.5 servings per day. This reflected equivalent intakes to 250ml milk, 20g cheese, and 100g yoghurt, providing 562mg/d additional calcium and 12g/d protein. Thus, the achieved daily calcium and protein was 1,142mg/d and 1.1g/kg/d, respectively.

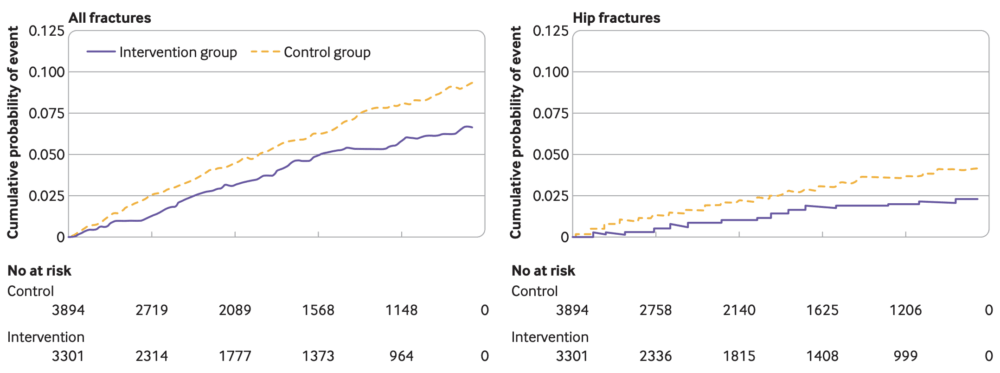

Over an average of 12.6 months follow-up, there were 121 fractures in the intervention arm and 203 in the controls. Compared to controls, the intervention had a 33% [HR 0.67, 95% CI 0.48 to 0.93) lower fracture risk. The risk of hip fracture was 46% [HR 0.54, 95% CI 0.35 to 0.83] in the intervention arm. The difference in risk of fractures became significant 5 months into the intervention. You can see the survival curves from the paper, below.

But What About Vitamin D?

It’s hard to overstate the major methodological strength of the Iuliano et al. trial for a nutrition intervention: deliberately targeting participants with likely inadequate, or at least suboptimal, levels of nutrient intake. This provides a study with a greater likelihood of detecting true effects of the nutrients of interest. However, another crucial methodological characteristic of the trial was that vitamin D was held constant throughout the trial. Baseline 25-hydroxyvitamin D, the plasma marker for vitamin D status, were 72nmol/L, which is more than adequate. Thus, adults had sufficient vitamin D but insufficient protein and calcium.

Why is this important?

One of the issues in teasing out the effects of calcium on bone health is that calcium is mostly supplemented alongside varying doses of vitamin D3. Indeed, a meta-analysis by Boonen et al. demonstrated that positive effects of vitamin D supplementation are only observed when calcium is supplemented alongside vitamin D. This interaction is often cited to suggest that there is no effect of calcium alone. However, participants in these studies often have insufficient vitamin D levels.

This is important as the relationship between the risk of fractures and 25(OH)D levels may be non-linear and is primarily observed below levels of 70nmol/L. This range of 25(OH)D levels is also the range at which maximal intestinal absorption of calcium is observed. Generally, the benefit to the modifying effect of vitamin D on calcium is that vitamin D up-regulates calcium absorption, allowing for a lower threshold of dietary calcium intake.

However, what happens when vitamin D is sufficient but calcium is insufficient? The Iuliano et al. paper addressed that question. By maintaining vitamin D constant and having blood levels of 25(OH)D at which we would:

- Expect to see maximal effects of vitamin D on bone health, and;

- Expect to see maximal intestinal calcium absorption.

By achieving this contrast, increasing calcium intakes from insufficient levels while vitamin D status was sufficient, their paper provides evidence of independent effects of calcium and protein that have been previously difficult to determine.

Don’t Forget About That Protein

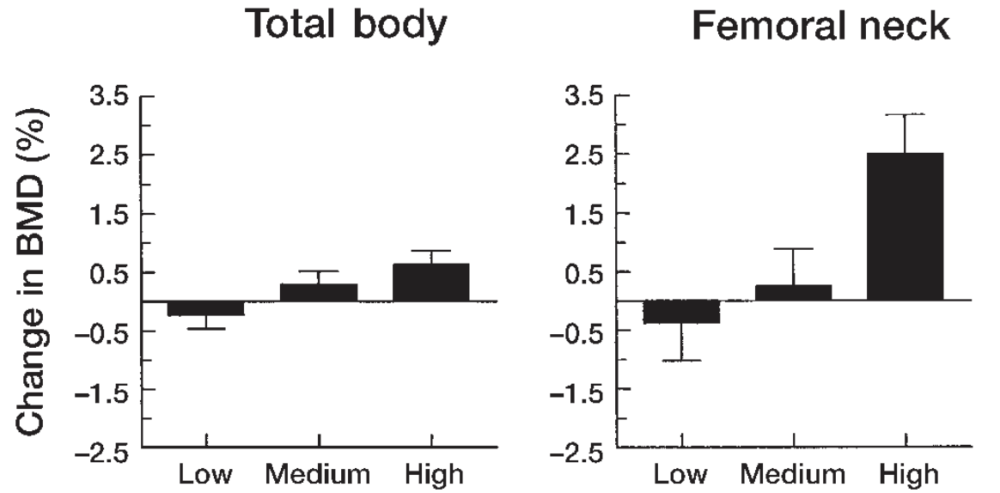

By holding vitamin D constant, the Iuliano et al. paper highlighted an interaction between dietary protein and calcium that may be just as important as the interaction with vitamin D status. Dietary protein is a crucial mediator of intestinal calcium absorption, and previous research has shown that diets with <0.8g/kg dietary protein increase calcium losses. Dawson-Hughes et al., in an analysis of the WHI trial, showed that among participants supplemented with calcium + vitamin D, those with the highest protein intake had the greatest increase in bone mineral density.

In the figure above from the paper, the analysis stratified the outcomes of total body bone mineral density [left] and femoral neck bone mineral density [right] by tertiles of dietary protein intake – low, medium, and high. This was a reflection of their habitual dietary protein intake in the context of participants supplementing 1,000mg of calcium and 400IU of vitamin D per day. As you can see in both graphs, those with the highest dietary protein had the greatest positive effect, highlighting the modifying effect of dietary protein with calcium.

Thus, the achieved protein levels of 1.1g/kg/g in the Iuliano et al. study were arguably crucial to the effect of calcium on bone outcomes, building on prior research suggesting the combination of these nutrients may have additive effects on bone health.

Final Points for Context

The context of the very elderly population in full-time residential care with substantial comorbidity in this study is important to consider. The study targeted a particular population, and it is important to note that the average age of the participants was 86 years. As stated above, this was a population with substantial comorbidity, with 66% of participants in both groups at risk of malnourishment, 52% with cognitive impairment, and 65% with cardiovascular disease. This is a population at high risk of osteoporosis and fractures, so the choice of population is justifiable.

However, it is an important caveat regarding wider potential applications. In the context of RCTs based in residential care homes, 1,200mg calcium and 800IU vitamin D3 have previously resulted in reduced risk of fractures in subjects over 70 years. Nevertheless, the Iuliano et al. paper provided additional context to an ongoing area of debate.

First, their study was a food-based intervention and therefore has more immediate wider application. Second, vitamin D was held constant throughout the trial, and this points to a real effect of the additional calcium and protein provided by the additional dairy foods. Finally, the levels of intake – 250ml milk, 20-40g cheese, 100-200g yoghurt – are readily achievable for the elderly. Given the low levels of calcium and protein common even in the > 65 years age group, this study likely has important application to a wider elderly demographic.

So yes, it does appear that calcium is important for bone health and reducing fracture risk in the elderly, exerting direct effects on skeletal function. The best way to think about vitamin D is as an indirect modifier of the direct effect of calcium, and it may be that protein exerts just as important an indirect modifying effect on calcium to improve bone mineral density and lower fracture risk.

Yours in Science,

Alan

Learn with Us.

You’ll find our most comprehensive resources in the Alinea Nutrition Education Hub.

Our weekly Deepdive takes a take a forensic look at a recent study: you’ll understand the background, the findings, and the relevance of the study in the context of the wider literature.

Our bi-monthly video Research Lectures condense complex topics into a visual presentation for you to maximise your learning experience.

And Exclusive Articles from researchers and academics in the field of nutrition science provide insights and perspectives from the people producing the research.